WRITINGS /

Criteria for Design in the Arabian Gulf Region

Criteria for Design in the Arabian Gulf Region

"This is contradictory to all values of Islam, this is an Islamic country. You have produced houses for American families. They are not for Arabs, the people of Islam.”

The process of starting each project from scratch becomes a wasteful and tedious exercise at the best of times, but even more so in a fast developing area like the Gulf where the pace of work required does not permit the architect the luxury to think out each problem in the depth necessary.

To be able to cope intelligently with this recurring problem, a general list of criteria must be developed to assist the architect to check and come to grips with the alternatives facing him. Although pages can be written about any individual criteria listed, brevity has been preferred, as most practising architects tend to prefer a short, usable checklist against a long scholarly treatise on the subject. The criteria listed in this article were done so with housing in mind, but with modifications they have also been used successfully on other types of projects.

(1) Design to meet a client's requirements. This statement is fairly clear. However, it is necessary to elaborate on the following specific aspects of it that must be dealt with before beginning the design of a project here.

The first is never expect a clear and complete brief. A two-page statement of intent for a $50 million project is not unusual, probably because the majority of clients will be building a structure of this type (e.g. an airport) in the country for the first time. So help the client develop a detailed and realistic brief.

Secondly, when one finds oneself in this position, do not blindly use western space standards. It is better to check and see if a similar project has been built elsewhere in the region, study it, and interview the staff who manage it. This will greatly increase the chances of discovering behavioral patterns unique to the area (e.g. the need for large public check-in areas to accommodate the families and friends that accompany most passengers at airports). The third is to try not to be overly upset by a client's constantly changing needs and time schedules. This is usually brought on by the very common 'trial and error management approach' used here. Accept it as a basic fact one must live with in harmony.

(2) Respond positively to the realities of climate and orientation, especially the harsh sun and wind-borne sand.

The first concern here is the proper use of shading and insulation to reduce the heat gain of a building.

To achieve this, one has to deal with two types of heat transfer: the first is the penetration of direct sunlight into rooms, which can easily be controlled with proper shading; the second is direct heat transfer through the walls and openings, irrespective of orientation. Deal with this by minimizing glass areas, and always insulating roofs and external walls.

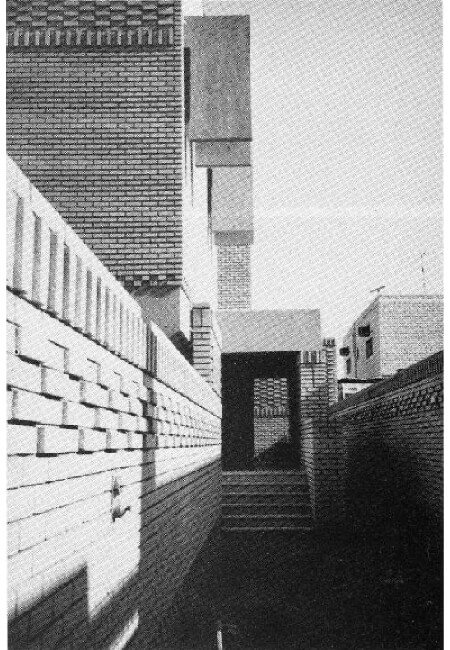

The second is the maintenance problems caused by fine wind-borne sand, that will penetrate most openings. One of the best ways to control this problem is either to deflect, or avoid the wind force, before it reaches any openings. This can be done by designing all window and door openings below the boundary wall level, and avoiding high-level windows on the external perimeter of the building.

(3) Encourage the use of regionally available building skills and materials. The uniqueness of each geographical area and regional character depends on this (e.g. Yemen). It also makes a lot of economic sense to do so, as many of the traditional building skills in brickwork, masonry, plaster work, woodwork, and even weaving will disappear within a decade, unless indigenous skills are encouraged and developed at all levels of the construction industry.

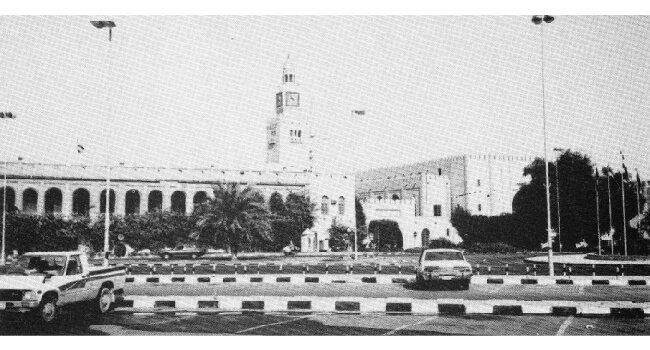

(4) Integrate the building into its environment. This is done to achieve visual harmony and a continuity of character of place.

The two basic controls for achieving this are as follows. First, the color of the material; try never to contradict the predominant color of the material of an area. The second is to integrate the building form with the existing environment, by not letting it dominate, nor stand out conspicuously.

(5) Avoid individuality for individuality's sake. Uniqueness is not necessarily a positive criterion of design.

Unfortunately, one of the great tragedies of the Bauhaus School of Teaching, that penetrated most contemporary schools of architecture, was its confidence in the creativity of the individual designer. A principle that encouraged most architects to look down upon the 'vernacular' as unworthy of their attention and placed unfortunate emphasis on the need for new 'creative' solutions to age-old problems (e.g. housing).

(6) Use geometry. This is crucial if one is to achieve aesthetic harmony.

Most vernacular architecture has an inherent geometric discipline imposed on it by either the structural or physical limitations of the materials used (e.g. the mud walls and mangrove poles used in the Gulf) that gives it a natural aesthetic harmony. As contemporary materials and technology rarely place such limits on architects, one must create this limit and one way to achieve this is by the use of geometrically repetitive and divisible structural and spatial modules.

(7) Create a variety of internal and external volumes. This is to attain a diversity of spaces in one's work.

To achieve this, design spaces with double, treble, and four-storey volumes, wherever possible. The quality and variety of the spaces created by the use of volumes in the vernacular are still valid today, irrespective of what the original use was.

(8) Enclose space as often as possible. This is one of the basic inherited principles of design that still makes sense.

This will not only help one relate one's structure to the tradition, but will also help overcome many of the problems of site design in a harsh climate. The courtyard house is not only a classic example of an enclosed space, but of one where maximum utilization of land is achieved because it is built on the boundaries of sites and not within them.

(9) Maximize changes in topographic levels. This is to create an interesting landscape.

As most sites here are relatively flat, it is imperative to take advantage of even the subtle changes in the topography, to create as many levels as possible, to enhance the quality of the environment created.

(10) Impose height limitations. This will protect the urban texture of an area.

Unfortunately, the extension by technology of the natural height one could build to, using natural materials (whether mud, brick, or stone) has completely destroyed the urban texture of today's cities, and the only way to counteract this trend is always to try to build nothing above three storeys high; as that is about as high as anyone would ever want to climb on foot.

(11) Use traditional motifs and symbols. This is necessary to relate the building to its heritage.

For many years, the only accepted symbol that immediately converted any piece of architecture into Islamic architecture was the use of arches in the elevation. Although it is tedious to be constantly confronted with this request, in time one comes to appreciate the desire in people to relate buildings to one's heritage. To achieve this, a number of traditional symbols can be used. Amongst them are:

(a) The use of a single harmonious building material;

(b) The visual expression and emphasis of doorways and entries;

(c) The mashrabiya treatment in wood for windows;

(d) The repetitive use of vertical walls, set back against each other;

(e) The use of intricate brickwork;

(f) Calligraphy, etc.

(12) When planting, work with nature, not against it. This is to maximize the use of what little water we have. One does this by the use of desert plants, proper shading, and the concentration of lush planting in small, easily maintained areas.

(13) Design simple infrastructures. This is to reduce and simplify the problems of maintenance and care.

A simple infrastructure is one that can be easily installed, needs little maintenance, and can be easily replaced, without tearing up the foundations or knocking the house down. (For example, locate drainage/sewage lines in an accessible duct instead of having them criss-crossing the floors of the major living areas.)

(14) Be maintenance conscious. This is to guarantee that the building will be well looked after.

One could write an entire book on the errors committed by architects in this context. For buildings designed for general public use, there is a simple rule of thumb. If floors, walls, and fixtures cannot be hosed, painted, or reached with a portable ladder, they will rarely get cleaned, repaired, or replaced.

(15) Renovate whenever possible. This is to preserve what little is still left of our traditional environment.

Whenever one gets the choice either to renovate or demolish, it is better to renovate. Too much has already been destroyed and what little can still be renovated and conserved should be.

The above-listed criteria were developed from experience over the past 10 years and, although their application will not necessarily produce a work of art, it will produce a simple and practical building that is sympathetic to its environment.

In the long run, however, no criteria will help, unless one acquires a thorough understanding of how things are built, and this can only be achieved by constantly visiting sites to learn as much as possible from the contractors and the craftsmen in whose hands ultimately depends the final outcome of one's efforts.

Received 12 May 1981; Revised 20 July 1981.

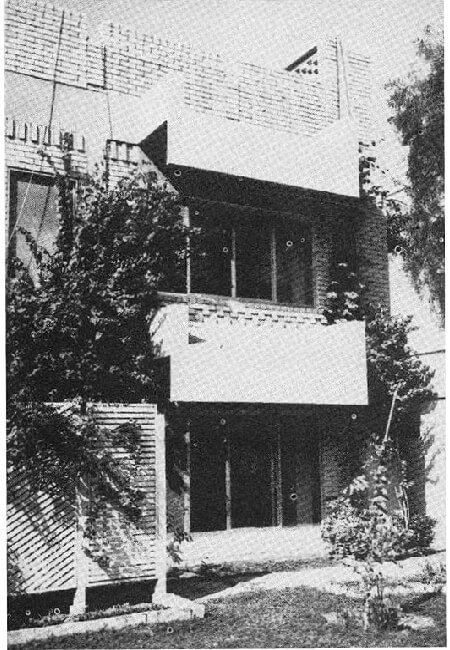

Figure 1. Use of Shading on Southern Elevation

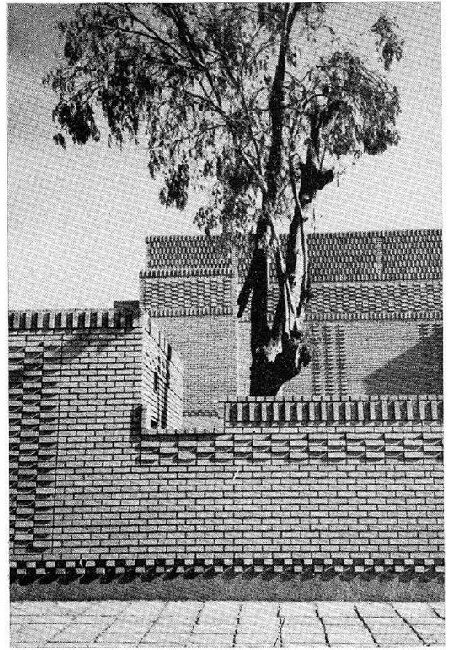

Figure 2. Solid Wall to Prevent Sand Penetration on North-west Elevation. All Windows are Situated Below the Boundary Wall

Figure 3. Intricate Brickwork on Boundary Wall

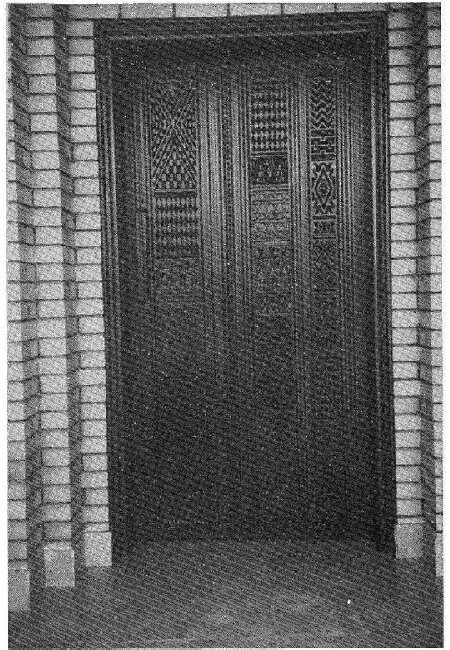

Figure 4. Creative Use of Bedouin Weaving Motifs on Carved Teak Wood Door

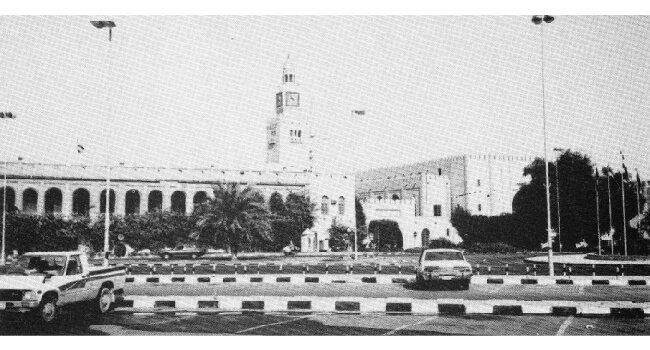

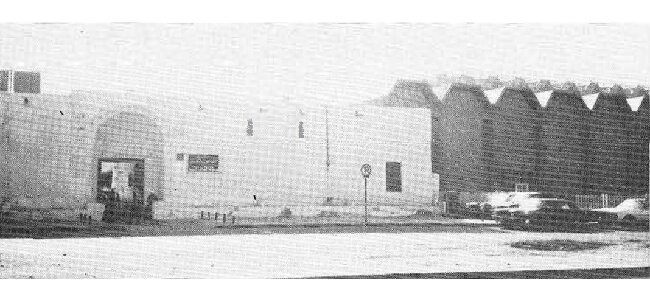

Figure 5. Contrast Between Old and New Museum in Kuwait

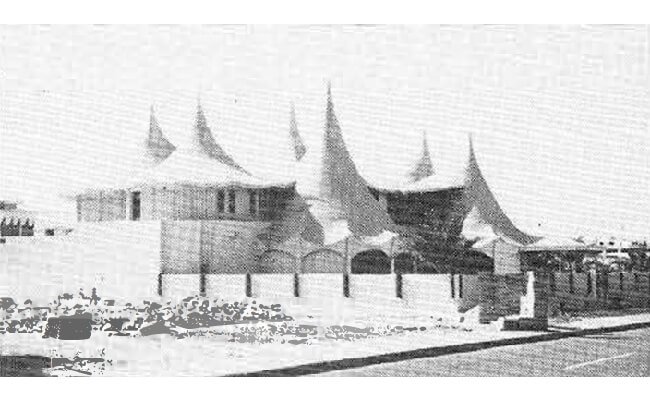

Figure 6. Concrete Tent Structure on Private Residence in Kuwait

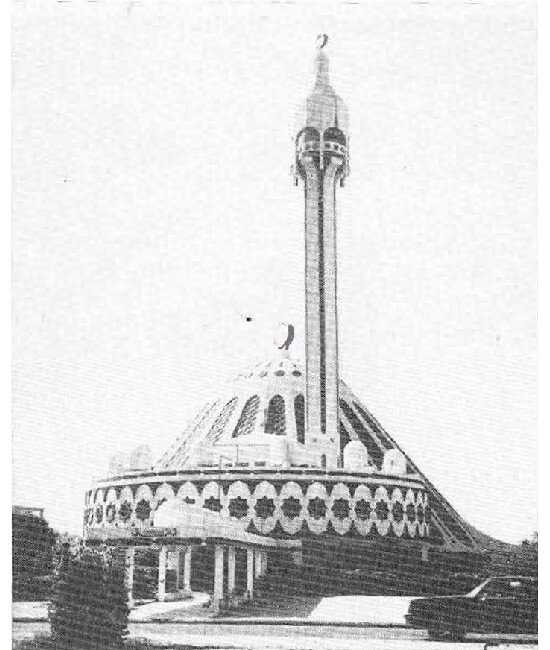

Figure 7. Fiberglass Mosque in Kuwait

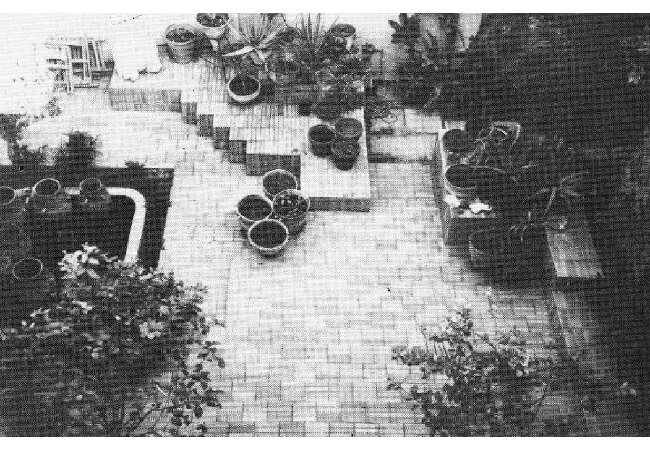

Figure 8. Use of Volumes and Levels in Private Residence

Figure 9. Small Private Garden Where +40 to -40 cm Height Difference is Used to Maximum Advantage

Figure 10. Difference in Scale between Existing KF AED Headquarters and the New Highrise Extension

Figure 11. Use of a Single Harmonious Material and Vertical Walls on a Private Residence

Figure 12. Brick Expression and Emphasis of Main Entry to a Residence

Figure 13. Brick Expression and Emphasis of Main Entry to a Residence

Figure 14. Good Integration of of Old and New Structures at Sief Palace in Kuwait